Nature journaling is a wonderful practice for people of all ages. It sharpens our curiosity and our skills of observation, drawing, and writing, all while we soak in the beauty of the outdoors. Nature journals can be anything from sketchbooks to detailed diaries about the birds, plants, animals, and other things we see around us, as well as how the seasons change them. I kept a nature journal from the ages of five to seventeen, and though in recent years I’ve lost the habit, today I dove into the archives of my journals to salvage the best scraps and suggestions to share! Reviewing my old journals has inspired me to begin again my nature journaling practice.

Ideas from My Kindergarten-1st Grade Journal Entries

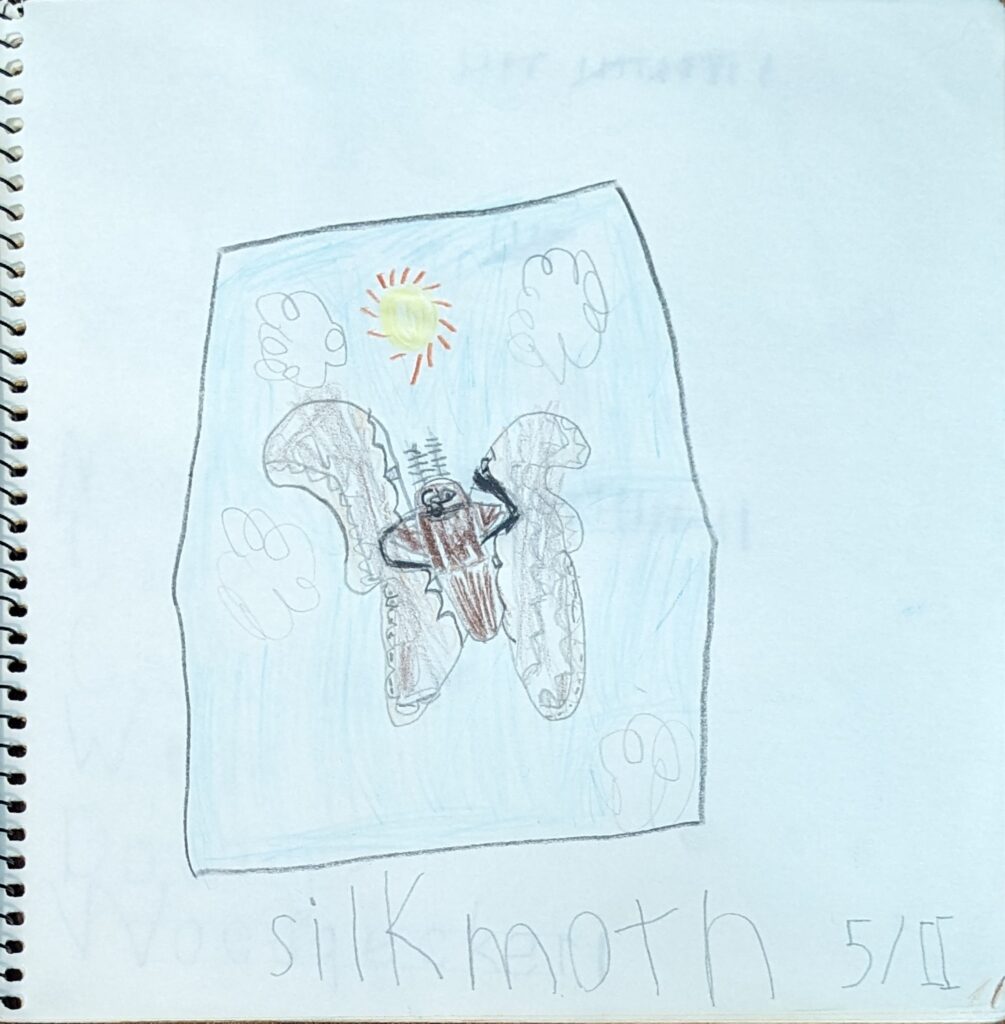

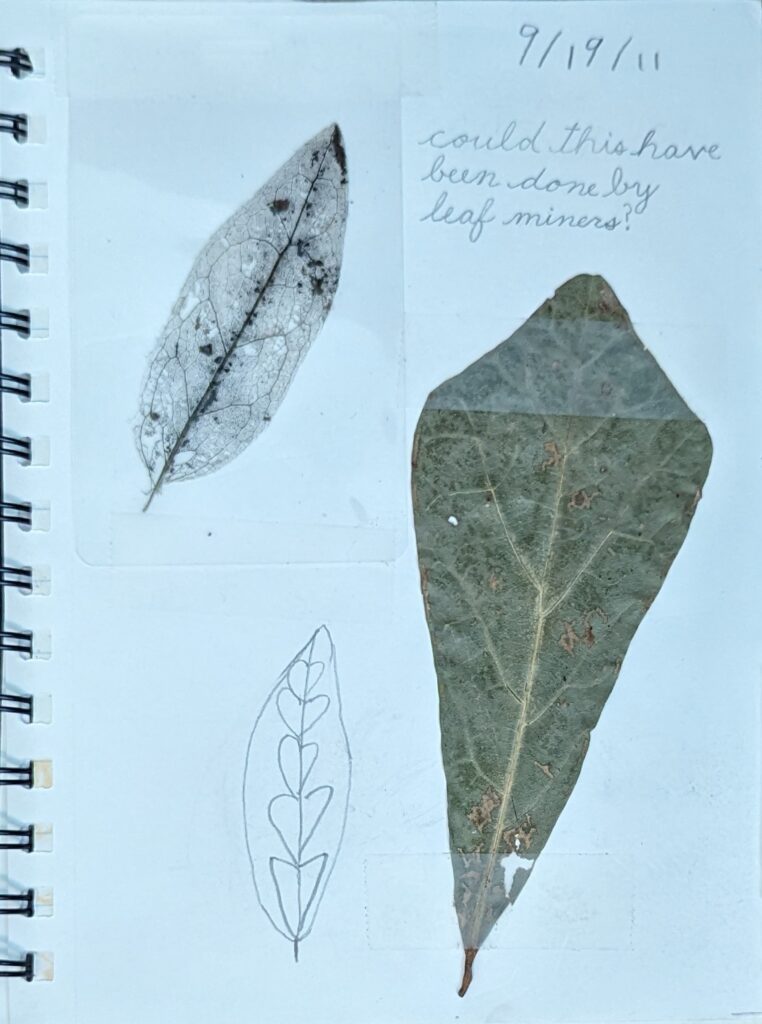

- Most of my earliest entries were simple drawings of anything from a specific kind of moth that we discovered in the backyard and identified, to a spider, to a lizard egg that I found on the ground. There are so many things to find– you don’t have to stick to trees or even birds! It’s rewarding to learn the names of the plants and creatures that are your neighbors.

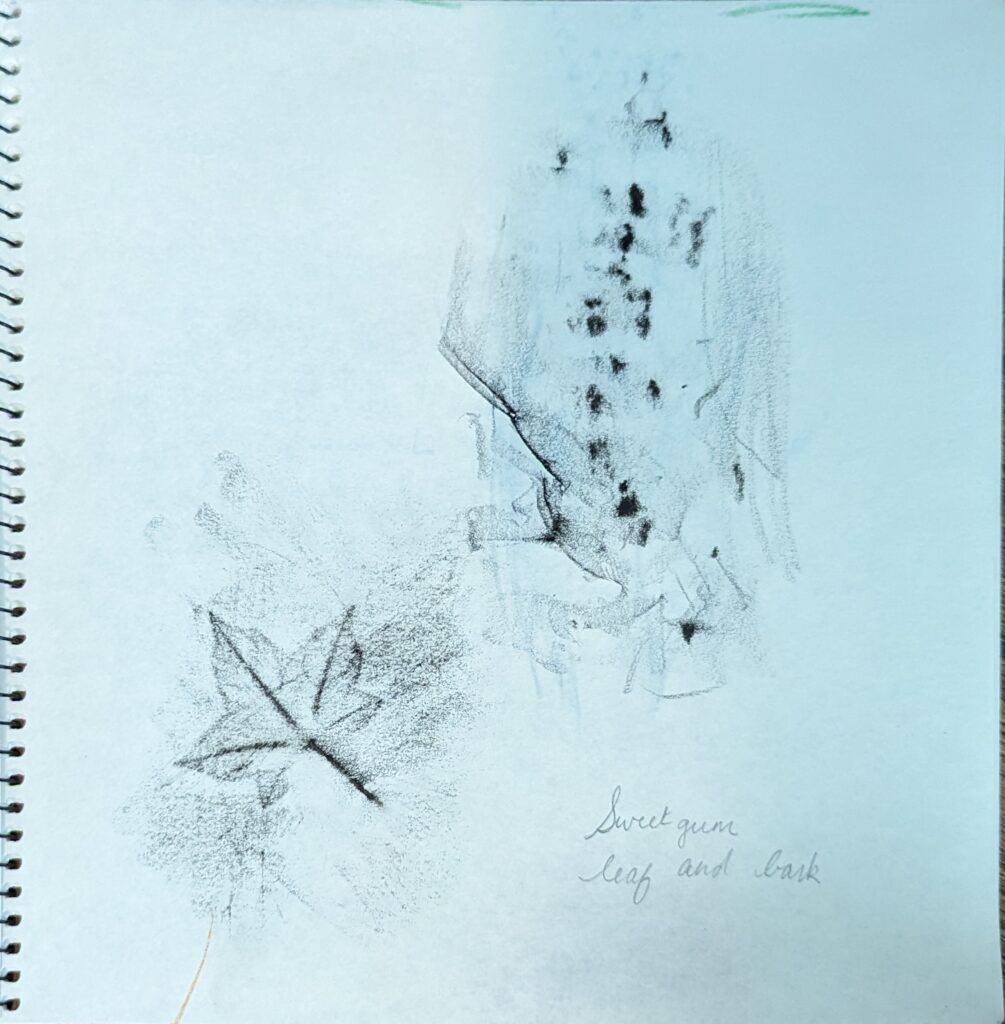

2. Leaf and bark rubbings are a wonderful, easy project for a young journal keeper. Simply press a leaf underneath a sheet of paper and rub over it with a large crayon, a pencil, or a stick of charcoal to capture the shape of the leaf, and the details of its veins and edges. You can also do bark rubbings; many species of trees have distinctive and interesting bark textures. Be sure to label your rubbings with the name (and Latin name, if you like) of the plant that it came from!

3. Pressed leaves and flowers are also simple and rewarding. You can buy a flower press for this purpose, but you don’t have to. Placing the leaf or flower between two thick pieces of white paper and leaving it for a few days between some heavy books will do the trick. You can then tape or glue the pressed result into your journal! I also found some butterfly and moth wings in nature after the insects had passed away from natural causes and taped them into the pages of my notebooks. Again, be sure to label anything you preserve!

4. Since my early years I kept a weather chart, with a row for each day in a month, and columns like “Rain,” “Windy,” “Cloudy,” “Sunny,” and “Temperature.” I would put a check mark in each column that applied on a given day and write in the temperature.

5. Finally, I had a bird-watching tally: in one sitting, we counted sixteen chipping sparrows, five American robins, twelve mourning doves, five Carolina wrens, and one downy woodpecker. For people with a longer attention span, and especially for those with access to a bird feeder, this exercise can help you learn the names of some of your visitors, and even learn to spot the differences between similar species.

From My Elementary-School Journal Entries

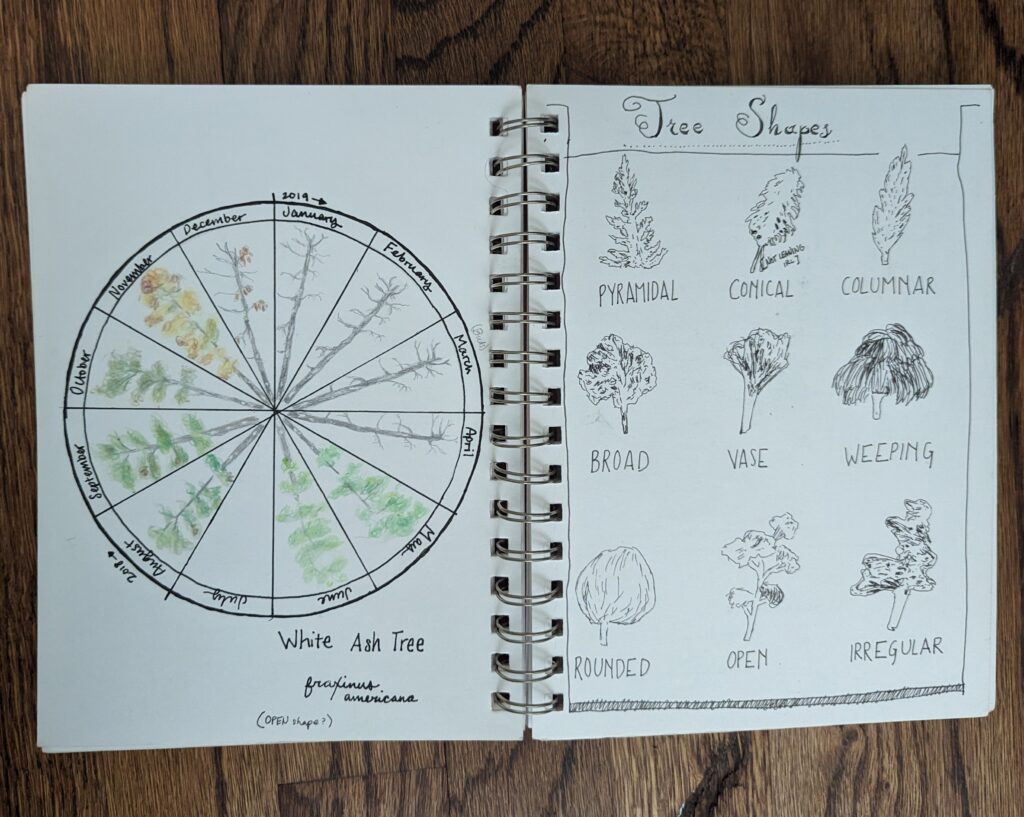

6. Choose a tree and follow it through the seasons. You can draw it at least once every season– more often, if you’d like– and track significant days, like first buds, first green leaves, and first fallen leaf or first bare branch for deciduous trees. You can also name them! (I named my trees Dick Whittington and Rowena, for reasons lost to time.)

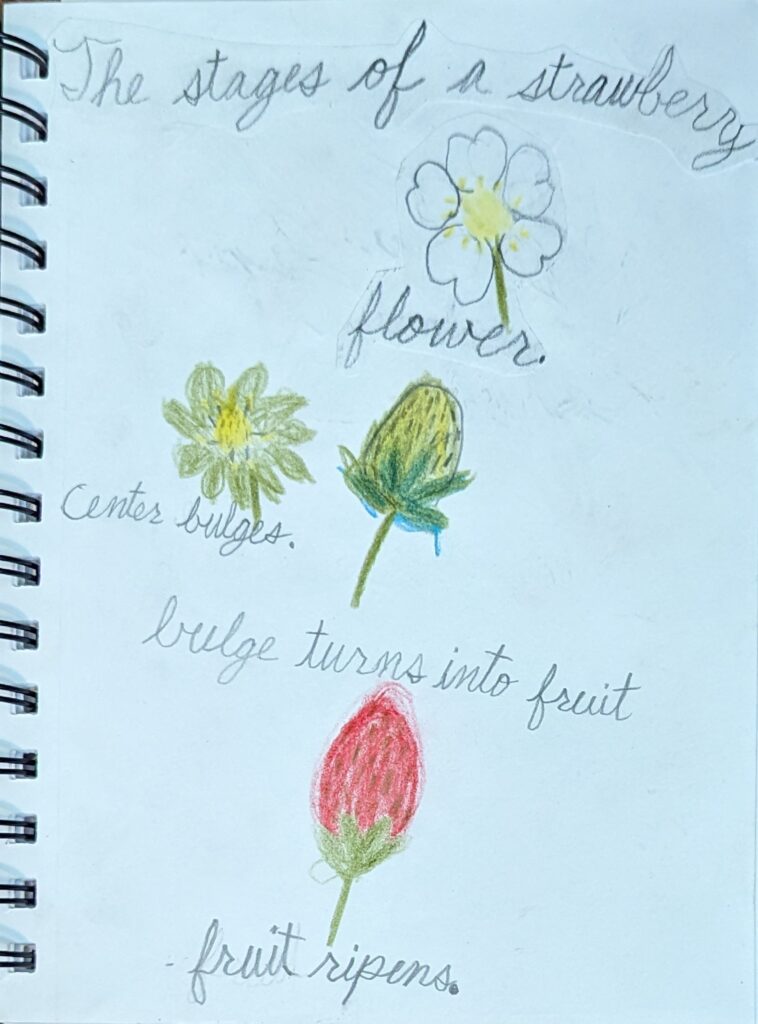

7. Drawing the life stages of a flowering plant, like a strawberry, is a similar exercise that requires less commitment but can be just as rewarding. You can also draw the life stages of a frog, a dragonfly, or anything else you choose– preferably a species that you’ve just observed in person.

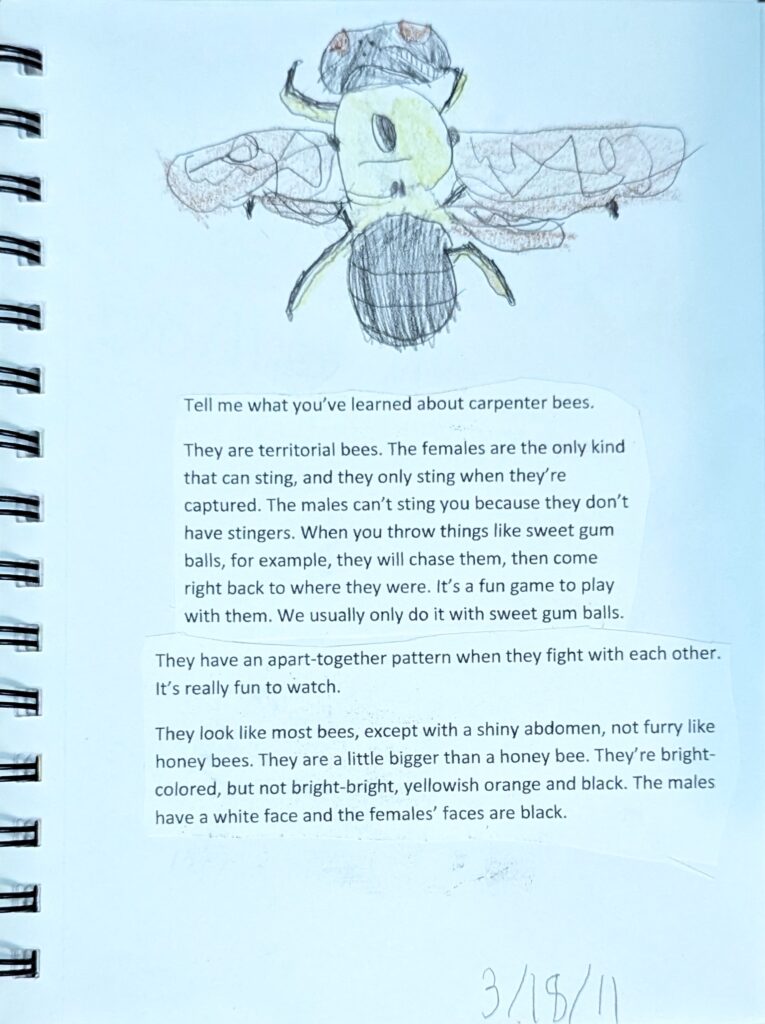

8. Sometimes, dictating descriptions of what you have learned about a plant or creature you find, or how that plant or creature looks, can be a helpful practice, especially if you write too slowly to describe things in depth. My mother sometimes wrote out my words by hand, and other times printed and pasted a typed dictation into the journal.

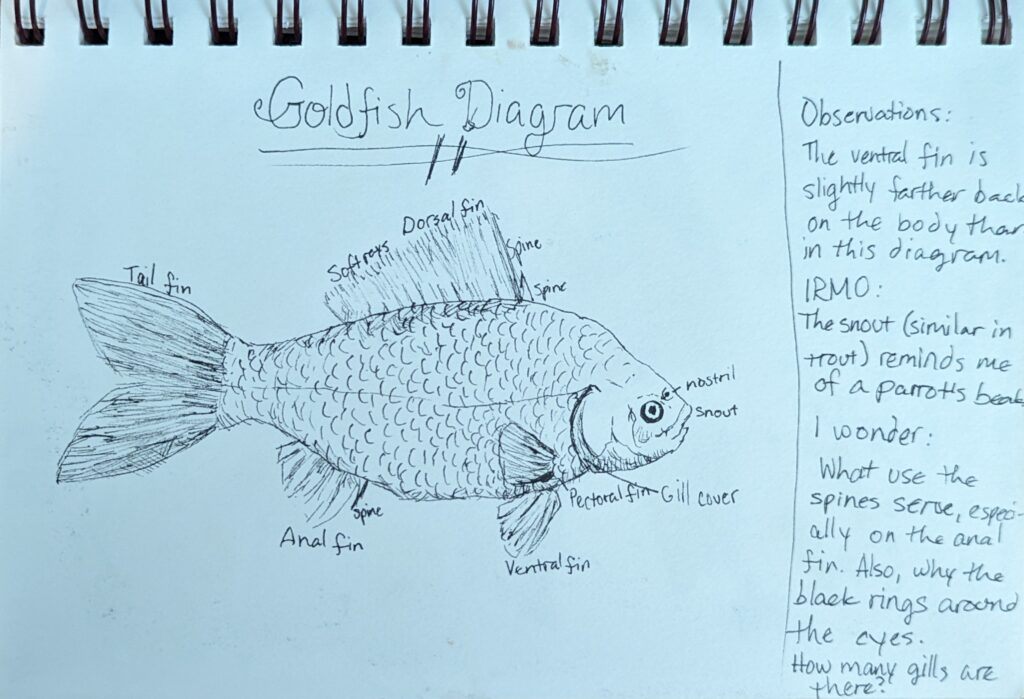

9. Diagrams are also wonderful additions. Fish, flowers, birds, beetles, wasps, leaves, mushrooms… diagrams can range from simple to highly detailed, and they can include descriptions of things such as the color and texture of features and variation between species. Diagrams also help teach vocabulary that can be useful in identifying and describing new species.

10. I’ve never done this personally, but printing and pasting nature photos and writing descriptions of them on the page could be a great journaling practice for students who prefer photography to drawing or painting!

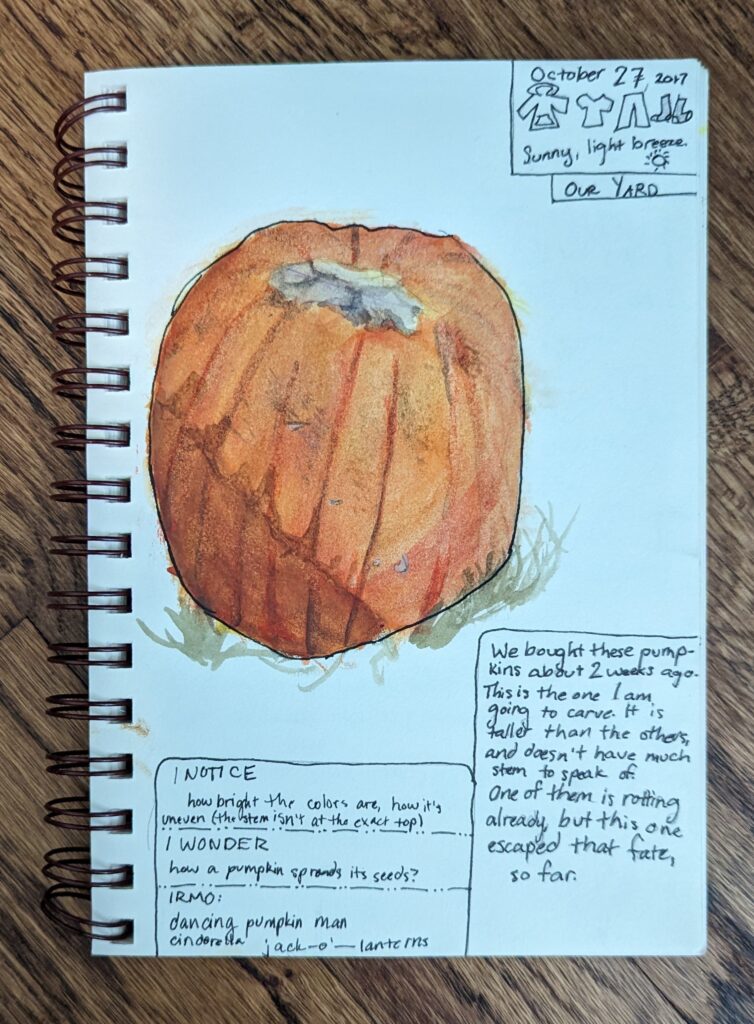

From My Later Journals

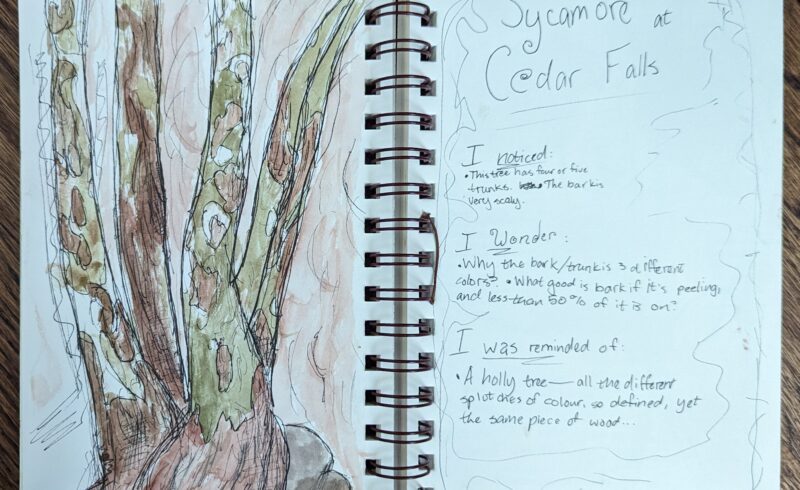

11. Many of my later entries follow a formula: I Notice x, I Wonder x, and It Reminds Me Of x. There is a lot more of my own handwriting in later entries, detailing colors and textures, questions and comparisons. I also began noting the weather in many of my entries, even when it appears irrelevant: weather might affect what kinds of creatures and plants are visible.

12. Bird-watching charts are another fun commitment if you keep up with them throughout the year. I kept a chart where I made note of the kinds of birds I spotted in each month. Learning to identify birds by song as well as sight can help fill out such a chart, especially if you don’t have a bird feeder handy.

13. Supplementing drawings with experiments in new art media such as watercolor painting or pen-and-ink shading can be a great way to up the complexity and precision of a nature journal entry. Watercolors mix nicely and are pleasantly affordable, even if they can be somewhat difficult to work with. India-ink pens are elegant and precise, and various pen shading techniques allow for distinct textures. Oil pastels are also a good option, since they are easy to work with, and provide vibrant, rich colors.

14. An occasional nature poem doesn’t hurt. Some of my favorite poems that I’ve written are just descriptions of something in nature, like the magnolia tree in my front yard. My middle-school nature poetry won’t leave the obscurity where I found it, but putting your observations into verse can be a wonderful creative endeavor.

15. My college advisor, a creative writing professor, recently gave me a piece of advice for learning to see and describe the world: every day, write down five things you saw, five things you heard, and five things you did, along with a drawing. A daily noticing habit along these lines, specifying things you saw/heard/did (or felt or even tasted) in nature, could make for an excellent skeleton of an advanced nature diary.

Adults Can Keep a Journal, Too!

Keeping a nature journal as a student improved the precision and detail of my drawing and paintings, helped teach me to describe the look and feel of things (especially natural things), and even helped me learn about identifying birds, bugs, plants, flowers, and more. I’m grateful that my parents encouraged me to keep such a journal, and I plan to start one up again soon. It’s something I highly recommend to anyone who wants to sharpen their eyes and learn to love the critters and plants, the tiny and the grand things, that are all around us, by knowing them by name and observing them with care.

Some examples of published “nature journals” or natural observations to use for inspiration include Janet Marsh’s Nature Diary, a beautiful book full of watercolors by the author, 1979; Susan Fenimore Cooper’s book Rural Hours, a description of the changing seasons day-by-day published in 1850; Middlewood Journal created by Helen Correll (2012), which documents the Piedmont woods with drawings, paintings, and essays; The Lay of the Land by Dallas Lore Sharp, 1908, another daily journal of nature observations; and The Handbook of Nature Study, 1912, an illustrated reference guide by Anna Botsford Comstock.

1 Comment

What an excellent and informative article!